🇰🇪 Kenya: A Luxurious Journey Through Culture, Wilderness & Coastline Magic

By Dante, 2 months ago

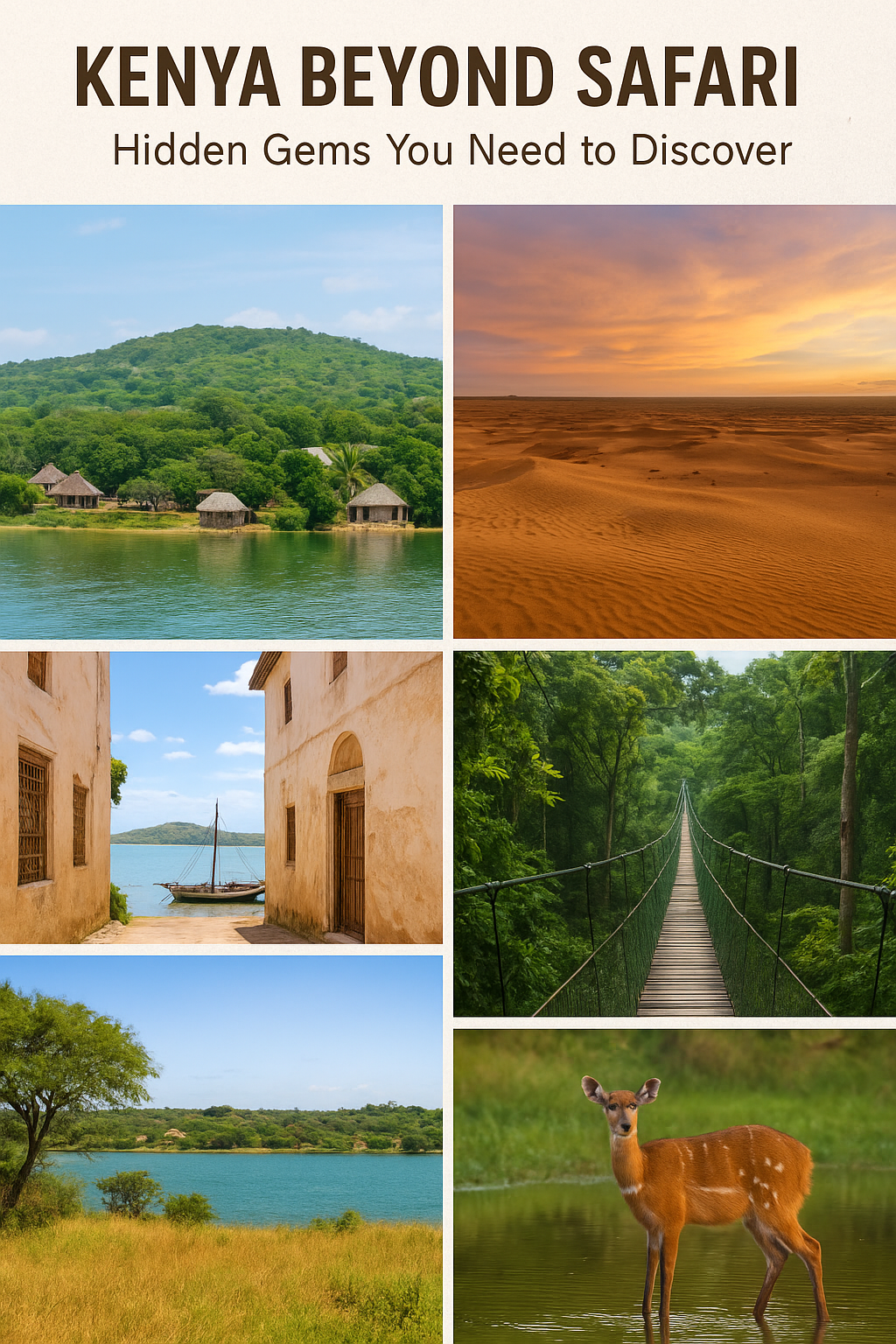

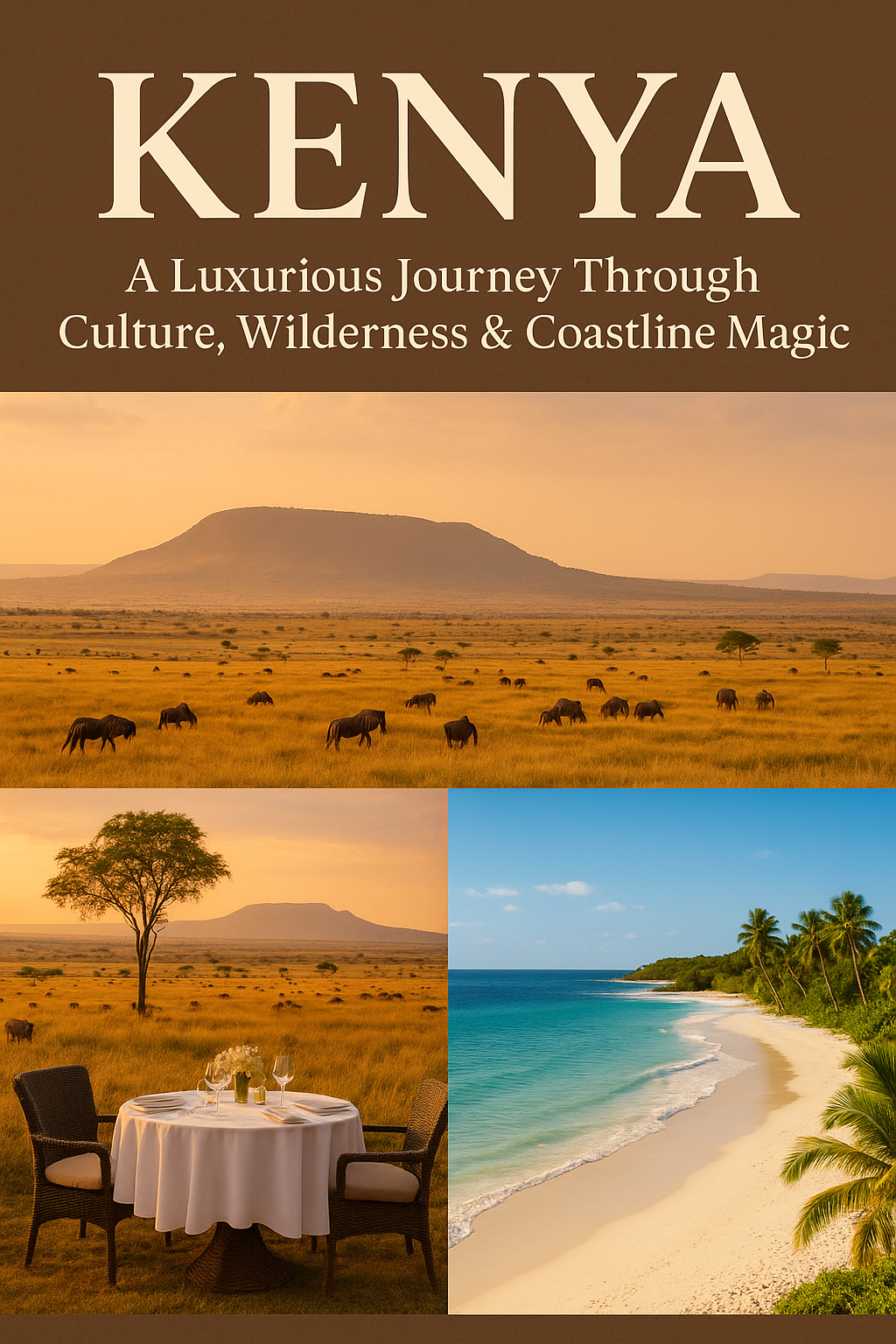

Kenya is not a destination you simply visit — it’s a world you step into. A world where ancient traditions breathe beneath the surface of modern cities, where amber sunsets fall over endless savannas, and where the Indian Ocean whispers against white sands as dhows glide gently across the horizon. This is a land of contrasts and harmony. A place where adventure and indulgence live side by side. And for the discerning traveler, Kenya offers a rare balance of luxury, authenticity, and soul-stirring experiences. ✨ The Spirit of Kenya: Where Culture Welcomes You First Before the wildlife, before the beaches, it is the Kenyan people who make your journey unforgettable. From the Maasai herdsmen adorned in crimson shukas to the Swahili artisans carving centuries-old designs along the coast, Kenya’s cultural tapestry is one of diversity, warmth, and timeless charm. Hospitality is not a service here — it’s a way of life. Expect to be welcomed with: Genuine smiles that feel like old friendships Food prepared with heart — from coastal pilau to countryside nyama choma Rhythms of Benga, Taarab, Afro-Jazz, and Genge filling night markets and city lounges Traditions deeply rooted in community, storytelling, and heritage In Kenya, culture isn’t observed; it’s lived. 🌍 A Country Designed by Nature & Refined for Luxury Whether you’re exploring the wild plains of the Maasai Mara, sipping champagne beneath Mt. Kilimanjaro’s snowcapped crown, or unwinding at a secluded coastal villa, Kenya delivers an experience infused with elegance and wonder. Let’s step into the most exquisite destinations this country offers. 📍 Destination Inspiration: Kenya’s Most Breathtaking Places 1. Nairobi — Africa’s Capital of Style Vibrant, fast-paced, unexpectedly cosmopolitan — Nairobi is more than a gateway; it’s an experience. Imagine having wild giraffes grazing at the edge of the skyline, just minutes from rooftop lounges and award-winning restaurants. Signature Nairobi Experiences Sundowners at Nairobi National Park Private breakfast with giraffes in Karen Curated art tours through the city’s contemporary galleries Forest walks in Karura, one of Africa’s most serene urban escapes Where to Stay (Luxury) — Villa Rosa Kempinski — Hemingways Nairobi — Tribe Hotel 2. Maasai Mara — A Safari Fit for Royalty The Mara is where luxury safari dreams come alive — where the earth trembles during the Great Migration, and where golden grasslands stretch beyond the horizon. Imagine waking to the distant roar of lions, then floating over herds of wildebeest in a private hot-air balloon. This is pure, raw Africa… experienced with refined comfort. Stay in Style — Angama Mara: a clifftop lodge suspended between sky and savanna — Mahali Mzuri: Sir Richard Branson’s futuristic tented paradise — Mara Serena Safari Lodge: panoramic views with exceptional service 3. Diani Beach — White Sands, Turquoise Dreams Along Kenya’s southern coastline lies Diani, a world of powdery sands, palm-shaded resorts, and gentle teal waters. Here, life slows to a luxurious hush. Indulge in: Oceanfront massages Sunset dhow cruises Snorkeling over vibrant coral gardens Private candlelit dinners on the beach Where to Stay — The Sands at Nomad — Almanara Luxury Villas — Baobab Beach Resort (premium all-inclusive) 4. Watamu — Coral Reefs & Coastal Serenity Watamu is a whisper of paradise — calm, intimate, and breathtakingly beautiful. Loved by honeymooners and elite travelers seeking peace with flair. Highlights Turtle reserves Glass-bottom boat tours The mystical Gede Ruins Sunset paddling in Mida Creek Where to Stay — Medina Palms — Temple Point — Turtle Bay Beach Club 5. Amboseli — Elephants at the Foot of Kilimanjaro There is no image more iconic than Amboseli: giant elephants wandering past the towering presence of Mt. Kilimanjaro. This is the place for photographers, romantics, and travelers seeking soul-deep moments. Top Stays — Oltukai Lodge — Satao Elerai Camp 6. Lamu Island — Timeless Elegance by the Sea Ancient Swahili architecture. Narrow streets scented with spices. Dhows drifting across the ocean at sunrise. Lamu is not a place — it is poetry. 🎒 Exquisite Experiences Across Kenya Champagne balloon rides at sunrise Luxury drives through the Great Rift Valley Marine safaris with dolphins and sea turtles Private coastal dhow dinners Premium city dining in Nairobi Guided cultural immersions with Maasai and Samburu communities Every moment feels handcrafted. 💎 Where Luxury Meets Convenience: Travel Essentials Best Time to Visit June–October: Golden dry season, perfect for safaris July–October: Great Migration December–March: Beautiful beach weather Getting Around Private flights (Safarilink, Air Kenya) Luxury transfers Nairobi–Mombasa SGR (First Class recommended) Uber & Bolt in Nairobi 🌅 A 7-Day Luxury Kenya Itinerary Day 1–2: Nairobi Giraffe breakfast • curated art tour • fine dining Day 3–4: Maasai Mara Luxury safari • private balloon ride • sundowners Day 5–7: Diani or Watamu Oceanfront villa • dhow cruise • spa & relaxation 🌟 Final Word: Kenya is Luxury by Nature Kenya captures the imagination like few places on earth. It is a destination where the wild meets the refined, where adventure meets elegance, and where every sunrise feels like a gift. For travelers seeking beauty, serenity, and unforgettable stories — Kenya is the journey of a lifetime.